ATINATI, a non-profit foundation committed to promoting Georgian culture, operates both as a media platform (ATINATI.COM) and as a physical cultural hub.

ATINATI, a non-profit foundation committed to promoting Georgian culture, operates both as a media platform (ATINATI.COM) and as a physical cultural hub. Among its primary missions is the continuous development of its private art collection — now in its fifth year and consisting of more than 2,000 works spanning multiple mediums and generations of Georgian art, from early Modernism to today’s contemporary scene.

The ATINATI Cultural Center’s newest presentation, “ATINATI COLLECTION,” brings together selected works by two acclaimed Georgian artists of the international contemporary circuit: Andro Wekua and Thea Djordjadze, shown from the foundation’s private holdings.

Thea Djordjadze

Born in Tbilisi in 1971, Thea Djordjadze studied at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts before continuing her education at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. She currently lives and works in Germany and is widely recognized for her refined sculptural language and installation-based practice.

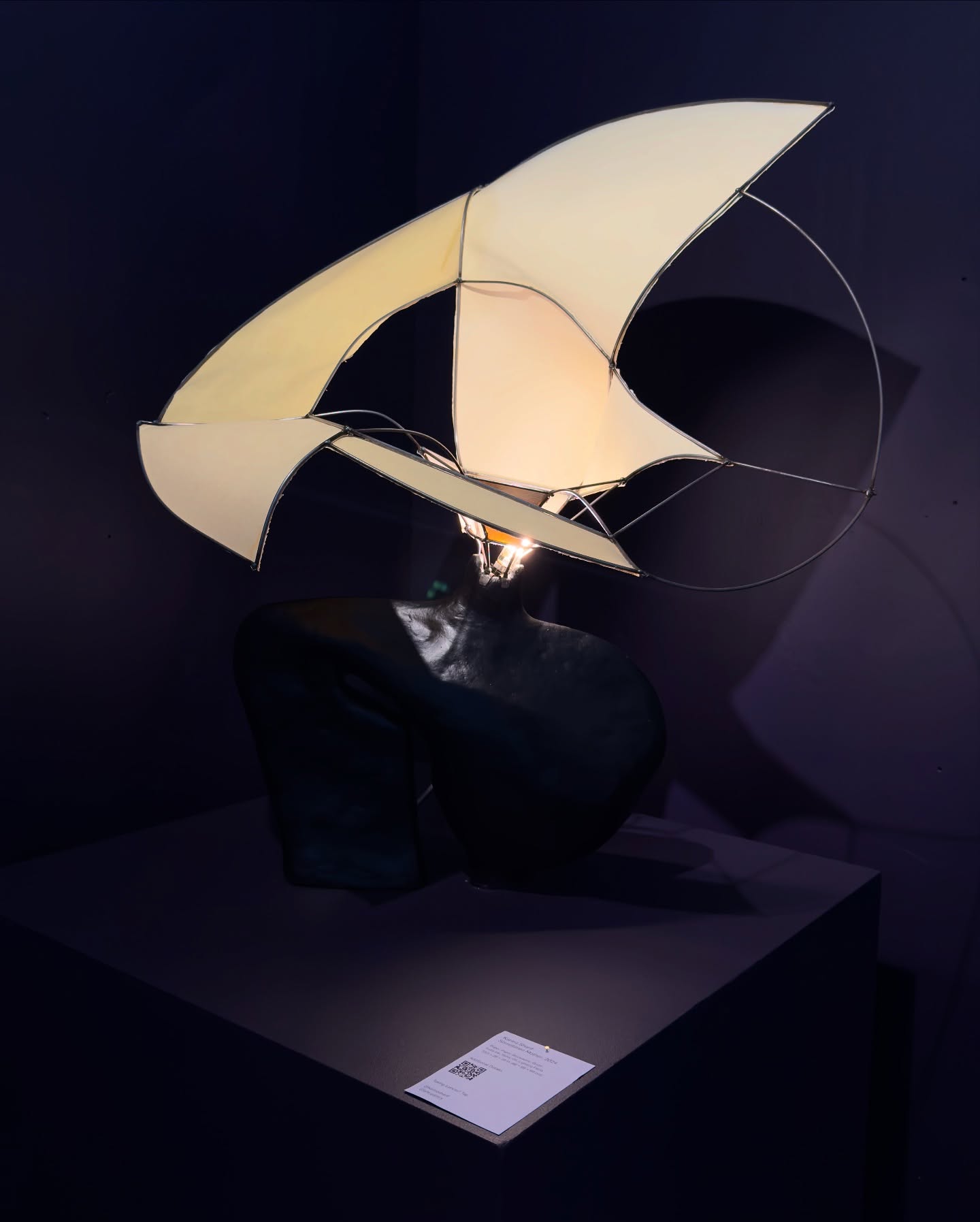

Djordjadze’s works blend materials that usually resist one another — metal frames, plaster, fabric, foam, glass, or wood — merging opposites into compositions that look both fragile and resistant. Her pieces often balance between abstraction and evocations of memory, private space, and cultural identity. Themes of impermanence and the traces left by experience recur throughout her practice.

The exhibited work features a slender metal skeleton that supports a soft, cream-toned textile folded loosely into the structure. This juxtaposition of rigid geometry and pliable matter creates an impression of constant shift, as though the piece might subtly transform at any moment. The delicacy of the foam fabric contrasts sharply with the firmness of the metal, suggesting a dialogue between endurance and vulnerability.

The sculpture avoids a specific storyline, yet it opens a broad emotional field: one might perceive it as a remnant of domestic space, a fleeting imprint of the human body, or a quiet meditation on the thresholds between interior and exterior. Djordjadze’s minimalist vocabulary allows her materials to speak in metaphor — body, architecture, and memory intersecting in a quietly charged form.

Andro Wekua

Born in Sokhumi in 1977, Andro Wekua is considered one of the leading Georgian contemporary artists working internationally today. His multidisciplinary oeuvre includes sculpture, painting, installation, graphics, and film. Much of his work is shaped by the loss and displacement he experienced after the Abkhazian conflict of the 1990s, when his family was forced to flee their home.

Wekua’s artistic universe sits between factual biography and dreamlike fiction. His figures frequently blend realism with imagination, hovering in a space where personal trauma merges with broader histories. His aesthetic is often described as atmospheric, melancholic, and surreal.

One of the featured sculptures — an aluminum branch painted with acrylics — depicts a magnolia, a flower common in Wekua’s childhood environment. What might seem like a simple botanical motif becomes a symbolic vessel for longing, recollection, and absence. The magnolia embodies both the beauty of the past and the impossibility of returning to it.

Another piece portrays a girl seated on the back of a wolf — a scene reminiscent of a myth or a hidden childhood memory. The girl’s stillness contrasts with the animal’s dark, protective energy. As in much of Wekua’s work, the image suggests an encounter between vulnerability and danger, innocence and instinct, humanity and the untamed world. It mirrors the psychological landscapes shaped by war, migration, and suppressed histories.

Wekua’s film included in the exhibition follows the visual language he has refined over years: interior rooms, landscapes, houses, animals, faces, and objects drift in suspended time. These motifs function like fragments of memory, weaving together personal recollections, collective trauma, and subconscious fears. The sequence culminates in the haunting image of a burning palm tree — a symbol interpreted as both a reminder of his childhood in Abkhazia and a monument to what has been forever lost.

The film blurs geographic and cultural boundaries, reflecting Wekua’s experiences in Sokhumi, Tbilisi, and Europe. East and West meet not in opposition but in a nuanced, intertwined continuum. With minimal gestures and a reserved palette, the artist constructs an emotionally dense meditation on time, displacement, and the fragile structures that hold one’s inner world together.